Understanding startup funding is critical for founders and investors alike, but fully grasping all the intricacies of funding rounds can be confusing for the novice investor. How, after multiple rounds of investing, do investors walk away with a profit? How much profit do they make? How is it all divided up?

Below is an overview of startup funding basics.

Most startups raise money in chunks—formally called rounds. When a startup initially kicks off, its founders aren’t approaching random angel investors or VCs. Instead, they’re typically looking closer to home, asking friends and families to open their checkbooks in support of their great business idea.

Right off the bat, founders incorporate their startup as a company. Then, they create shares of their company—stakes in ownership. The number of shares founders create is, for the most part, arbitrary, though they typically choose from 1M, 5M, or 10M shares.

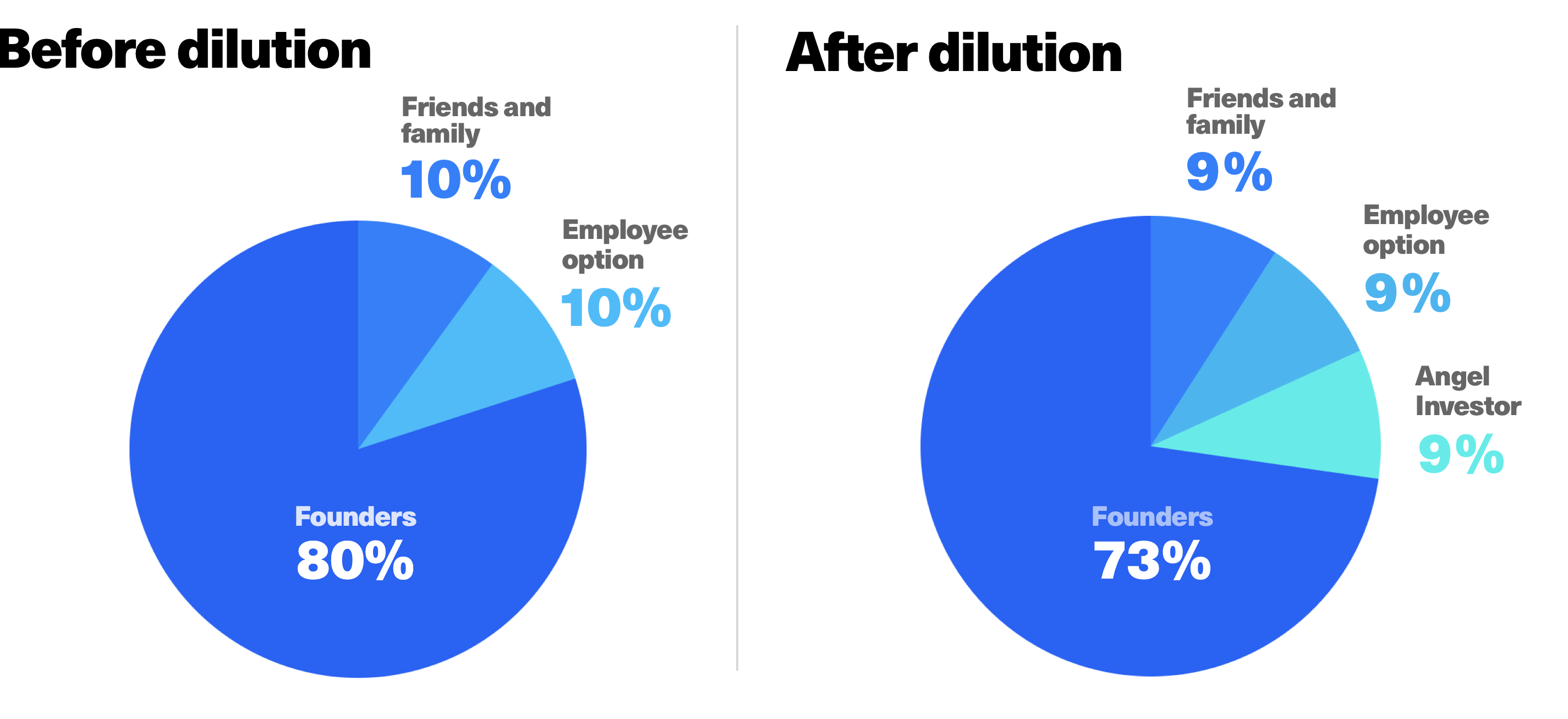

To illustrate this, we’ll create a fictional startup called ChocoRush, an on-demand service that delivers chocolate products to your door in under 30 minutes. It has two founders—Anna and Barry, and they create 10M shares when they found their company. Each take 4M shares, so together, they own 80% of the total authorized shares, or 100% of the company's outstanding shares. They set aside 1MM shares as an options pool for potential employees and leave another 1MM authorized—but not outstanding—shares, possibly to sell their friends and family for seed funding. Options are contracts giving employees the right to buy shares at a predefined price in the future.

The amount of shares the friends and family receive depends on how much each share is valued. If Anna and Barry raised $1M for their entire personal network and decide to value each share at $1, then the friends and family receive 1MM shares. This means Anna and Barry will own 8MM of 10M outstanding shares, of 80% of the company's voting stock, and their friends and family and potential future employees own the rest.

After Anna and Barry raise some money through friends and family, they’re ready to have a seed round of investment from either angel investors or through equity crowdfunding. At this stage, a beta version of their product or service might be up and running, and it may have even hit the market.

Angel investors are people who invest their own money into a startup, as opposed to VCs who invest other people’s money. Before the passage of Title III of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, an angel investor had be accredited, meaning they needed to have a net worth of at least $1M or an annual income of at least $200K for the last two consecutive years. With the passage of Regulation CF under the JOBS Act, there’s an exemption that allows anyone, despite their income or net worth, to invest within certain parameters.

Let’s say during a seed round an angel investor comes along and invests $1M. Now, Anna and Barry have to create 1M new shares to sell to the angel investor, so ChocoRush has 11M shares after the angel investor invests $1M.

The founders, their friends and family, and future employees owned 100% of the company together until the angel investor came along. The percentage of the company owned by the above parties will shrink slightly after the angel investor gets her shares. This process is called dilution. With each funding round, ownership by founders, employees, and investors shrinks.

With 11M shares, the founders own roughly 73% of the company, and the angel, friends and family, and future employees now own roughly 9%.

Though the dilution decreases both founders’ and investors’ percentage of ownership during each round, if the company has a large exit this won’t affect the size of their returns. For example, if founders start off owning 80% of a company with a $10M valuation but after multiple funding rounds only own 10% of the company at a $200M valuation, their returns increase from $8M to $20M.

There are three different instruments that are used in an unpriced round for simplicity, timeliness, and cost—the SAFE, the Crowd Safe, and the convertible note.

Safe stands for Simple Agreement for Future Equity. So when you invest in an early-stage startup on a Safe, you aren’t purchasing shares or equity. Instead, you’re purchasing a promise of future equity. It’s similar to the employee options in that Safes are contracts that give an investor rights to shares in the future. Let’s say an angel investor comes along and purchases $1M on a Safe in a seed round. Those shares do not convert to equity until the next fundraising round.

Investments on Republic are made through the Crowd Safe, which is similar to the Safe, except shares do not have to turn into equity until there is a trigger event—either an acquisition, a change of control or an IPO. The Crowd Safe shares convert into common stock at a trigger event.

Convertible notes are are a type of debt instrument that convert into equity. This means that convertible notes accrue interest and have a maturity date, which comes with much more tax-related paperwork. They are typically used in the early-funding stage, before priced or series rounds, but because of their complexities, more and more founders are raising money on Safes, even in the seed stage.

An investor’s convertible note converts into equity at a discount or with a valuation cap (which we’ll explain in further detail below), in the rounds following their investment, similar to the safe.

There are two types of shares someone can purchase when investing—preferred shares and common shares. Preferred shares can come with many different rights, such as voting rights and liquidity preferences. Voting rights allow investors to have a say in the company’s business decisions, and liquidity preferences allow investors to receive returns before those with common stock.

Those with common stock don’t have liquidity preferences or voting rights—service providers and employees in an option pool typically have common stock.

After the initial seed rounds of funding, startups begin to go through further rounds, and these are typically priced rounds, meaning investors are purchasing equity in the company by purchasing either preferred or common stock. They start with a Series A round, then move onto B, C, D, and so forth. Once a startup enters formal raising rounds, many different types of entities will often invest, from VCs to corporations, and sometimes even nonprofits and universities.

During priced rounds, founders and investors agree on a company’s valuation. Let’s say a VC firm invests $5M into ChocoRush. They agree with investors that the pre-money valuation of the company is $15M. The pre-money valuation of the company would be $15M, and the post-money valuation would be $20M.

Again, the founders have to continue to create new shares, which dilutes their percentage of ownership in the company.

When following funding rounds, one thing you may spot is reference to pre-money and post-money valuations. A pre-money valuation is the valuation determined prior to the amount raised. This is not the same thing as the valuation that follows funding of a previous round.

For example, if ChocoRush raised $2M in a Series A round at a pre-money valuation of $8M, the post-money valuation would be $10M. In the Series B round, the pre-money valuation will not necessary be $10M. Instead, investors and founders will agree on a new valuation. For example, they may agree to a $15M pre-money valuation in Series B. If Anna and Barry raise $5M in this round, the post-money valuation will be $20M.

Valuation caps are put on investment rounds to protect the investors in the case of a negative scenario, like a startup folding or getting acquired for a low valuation. In the case of ChocoRush, the valuation cap of $20MM could be placed on the Series A round. This means that if the subsequent rounds of funding has a post-money valuation of $30MM (which is greater than 20MM, the shares or equity from the previous round convert at the $20MM valuation, not the $30M valuation, leaving investors with a greater percentage of the company.

A discount means that when shares are converted in the next round the investor receives shares for a lower price than the investors in that round. If each share in the Series A round costs $1 and an investor invests $1M, in the next round those shares will convert at $.80 each. So the 1M shares becomes 1,200,000M shares.

In subsequent rounds of funding, investors’ shares convert at either the valuation cap or the discount, depending on what conversion is most valuable to the investor.

Exits are the whole reason people invest in startups. An exit is also called a trigger event, and it comes as either an acquisition or an IPO. When an exit occurs, investors are hoping their investment yields a very high return. If an investor put money into a unicorn — a startup that exists at $1B or higher — during its early stage, they'd receive a very high return. Still, some exits take the form of a liquidation or a dissolution—it's important to remember that startup investing is risky.

There’s even more lingo and complexity that we can dive into when discussing startup funding. This is just a primer on the basics. The most important thing to remember is that everyone wants to keep their cut of the pie as large as possible, and discounts, valuation caps, and purchasing preferred stock are some means that investors can do this. Most importantly, everyone wants a large exit.

This educational article is provided by Republic to help its users understand this area of the market, it should not be construed as investment advice as it is impersonal, disinterested and was produced by Republic for Republic’s users, without remuneration received or expected.

Oops! We couldn’t find any results...

Oops! We couldn’t find any results...